Eating

What is Eating Competence?

Greetings lovelies! I figured it was high time I wrote about this particular topic because I’ve been seeing lots of comments here and on Facebook about people having difficulty becoming internally regulated eaters.

Intuitive Eating is fantastic and it was one of the books I read early on after quitting dieting for good. It’s one way to learn to eat normally – meaning, listening to your gut (literally) when it comes to knowing when to eat and when to stop, feeling relaxed around food, and feeling confident that you are eating exactly what is right for your body. Notice I didn’t say anything about it being a way to lose weight or a way to learn how to eat less. I just want to throw that out there – continually – so nobody is confused about what this eating normally business is all about. It is NOT about weight loss. Ever.

Anyway, as I said, intuitive eating is one of the ways to learn to eat normally – but it isn’t the only way. In my diet-ditching literary travels, I came across other philosophies, ideas, and models of normal eating. I’ll link to those at the bottom of this post, but for now I’m going to talk about my absolute favorite model, Ellyn Satter’s Eating Competence. I’ve been doing some self-study on this model and re-reading some of her books, and I am reminded that this was the model that really clicked for me. If you’ve been struggling for a while with intuitive eating, I suggest looking at this or some other models for normal eating inspiration. For now, I’ll just talk about Eating Competence.

The Difference Between Eating Competence and Intuitive Eating

What is the difference between Intuitive Eating (IE) and Eating Competence (EC)? The essential difference, to me, is that IE focuses on eating-on-demand; that is, figuring out when you are hungry, eating exactly then, stopping when you are satisfied, and then starting the cycle all over when you are hungry again. Little is said about structured meal times and it favors listening to your internal regulation cues (there’s a bit more to it than just that, but for short form purposes, that’s the crux of it. Read the book for the full deal.). So IE seems to assume at least some connection with hunger. The problem is that most of my clients don’t feel their hunger.

EC also trains you to eat according to internal regulation cues, but relies on the discipline of providing yourself (and your family) rewarding meals at regular times, and the permission to eat as much as you like at each meal. Here is a more detailed explanation of the differences as written by Ellyn Satter herself. Both reject diet mentality and weight manipulation and embrace body diversity, both use internal signals of hunger and fullness to regulate eating, but one relies on meal-time structure and the other rejects it. I see both as useful models, but over the years I’ve leaned more towards EC because I see great results with clients finding relief with eating.

Structure is Positive Discipline

So how does this meal structure thing work? Learning to plan can help – but since we’re not planning to starve ourselves or trick our hunger, I view this as self-care, not external rule-following. You should count on providing yourself with at least three meals and three sit-down snacks (if you need them) a day, though even this pattern can vary. I often do a lot of work with clients on what schedule of eating works best for them.

The meals must be rewarding – you don’t want to spend a lot of time coming up with meals you don’t want to eat. You can start out with foods that are familiar to you and eat what is available. EC says very little on what you should eat, because this is a model that teaches you to eventually trust your body to guide eating.

With enough work, your eating eventually becomes internally regulated and you will learn to feed yourself well and feel good about this. Consider some of Satter’s books or working with a dietitian who understands this model (like me!).

You Have Permission to Eat as Much As you Want

I can’t emphasize enough that this model hinges on unconditional permission to eat – whatever and as much as you like. Beware of impostors that try to take away that permission, with rules like “eat a vegetable before the rest of your meal,” “fill up on water so you’ll eat less” or “sit and chew your food slowly.” No “tricks,” just permission. If you find yourself making food rules, always try to come back to this statement: “I can eat as much as I want.” You don’t need to be perfect, just honest with yourself.

If you’re struggling with internally regulated eating, just know you have some options. Do some investigation and experimentation, see what works for you, and go for it. You’ll eventually hit meal-time nirvana and never look back.

Dietitians Unplugged plug!

Episode 8 – The Beach Body Episode is available now! Listen on iTunes and Libsyn.

Start your path to normal eating with my free guide, 5 Strategies to Stop Overeating

Eating

![goat image by Andrew Hill [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons sheep and goat](https://daretonotdiet.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/sheep-and-goat.jpg)

More silly good and b-a-a-a-a-a-d: sheep go to heaven, goats go to hell. (bonus points if you guess the reference)

It would be just my luck that around the time that I finally gave up dieting and starting eating like a “normal” person (i.e., not feeling crazy around food, actually eating when I was hungry, not binge-eating), that the rest of the world would peak (let’s hope this is the peak) with disordered eating, including the classic “good food/bad food” dichotomy.

Years ago, when I first “changed my eating habits” (went on a diet), I kept it quiet. It was my secret fat shame that I felt I had to go on a diet (and this was back in the halcyon days where people didn’t feel quite so entitled to concern-troll fat people for their health. Ah, nostalgia!). So I told no one. I just stealthily lost weight and when people started to notice months later, I confessed I’d gone to Weight Watchers. None of this was for my health – I was 22! I was healthy just by virtue of being young! – it was just so I could fit in with the cool kids at last, and I didn’t feel morally superior for eating in a way that changed my body. If anything, I was amazed that I could still eat Nanaimo bars (look ‘em up) and regular cheese and mostly whatever else I wanted, maybe just not as much as I wanted. I kind of felt like I’d gotten one over on the whole damn system.

At least at first. When, as often happens with weight-centered interventions, I became dissatisfied with my smaller weight and body size, and at the same time my weight became harder to maintain, I decided to get even more restrictive. But to eat this way simply for weight loss or maintenance was not nearly enough motivation; I needed to feel virtuous, like an ascetic, to be able to tolerate such an extreme level of restriction. I ate “good” foods and shunned “bad” foods (unless I was off on a binge after caving into immense hunger) in the name of “health.” I would look at other people’s meals in restaurants, or what they were buying in the grocery store and sniff, mentally patting myself on the back for being so “healthy.”

I’m not proud of this behavior now. I was playing moral one-upmanship so I could feel better about going without. It didn’t really work (thus, binges).

Flash-forward to my totally normal eating habits now, in which I don’t overeat with any regularity (overeating accidentally is normal sometimes), and I don’t underfeed myself either (sometimes that happens by accident too). I don’t think about food all day long, I don’t plan my meals with extreme anxiety (rather, I plan my meals with joy in my heart and anticipation for the week to come!), I don’t simultaneously lust for and fear restaurant meals. I’m in eating nirvana, I tells ya! But having always been at least a step or two off from the rest of society, now I’m the normal eater and everyone else is the dieter!

It seems food, nowadays, is only seen in two ways: good (which is “healthy”) or bad (which tastes good). And if you are eating good foods, you are good. Likewise, if you are eating the bad foods, you are very b-a-a-a-a-a-d. Much like the assignment of feminine or masculine to words in the romance languages, in English we assign good or bad to all foods. The woman I overheard talk about forgetting her salad dressing said, “That’s okay, I have my homemade salsa – it’s healthier than my salad dressing. Salad dressing is bad.” When I asked how salad dressing was bad, she said it was because of the cholesterol (unless her salad dressing contained eggs, it likely didn’t contain much cholesterol, and that’s not even that important anymore anyway). Her homemade salsa didn’t have any fat or salt. Midway through her meal I heard her grown, “Ech, needs salt,” but even if she didn’t like her meal, at least she could feel good about her virtuous food choice!

I usually try to include some vegetables I like as a part of my lunch and someone will inevitably say, “Oh, you’re SO good.” (They will say the same thing if I take a walk after lunch, something I enjoy very much. For more about how I hate people “healthing” all over my exercise, take a listen here.)

At an office breakfast in which bagels, cream cheese, angel food cake and fruit were kindly provided, the person carving up the cake said, “It’s very light angel food cake so no one has to feel bad about eating it.” I couldn’t help but ask, “Are there foods that we should be feeling bad about?” I’m sure in everyone’s minds, there are! But what a shame.

Food choices don’t make someone a good or bad person, and assigning morality to foods based on their caloric content or macro- or micronutrient profile has only helped people to become more disordered in their eating, but not thinner or healthier (because those two things are not the same) as far the news reports.

So the next time someone tells me I am “good” for eating something they think is calorically virtuous, I’m going to tell them about my friend who was laid off from her job and then went on vacation…to help people get dental and medical care in Guatemala. Now THAT’S GOOD (and all her friends say so!). Eating quinoa instead of wheat or kale instead of candy does not make us good and it doesn’t help us to be good eaters either. Nope, it just doesn’t.

For a dose of hilarity on this subject, check out how Amy Schumer nails this BS:

Dietitians Unplugged Podcast Episode 7 now available!

Like our Facebook page to get all the latest news on our podcast and other non-diet podcasts. And if you like our podcast, please give us a rating and review on iTunes – this will help more people find us!

Subscribe and get my free guide,:

Why you overeat …and what to do about it

Click here if you just want my newsletter!

Eating

I was at a party a long time ago when a nice woman asked me what I did. I said I was a dietitian. She beamed and clasped her hands together and said, “Oh, that’s wonderful. Food is such medicine, isn’t it?”

I didn’t know how to respond at that moment. Food-as-medicine eating, for me, had at one point taken the guise of “clean”, local, organic eating all for my “health.” Really I was just finding new ways to restrict for my weight. I also had the vague sense that food purity might grant me immortality if I just did it right.

Behind all this was really just a desire to “fix” certain things that felt broken in my life. I was medicating today for a longer tomorrow in which I’d hopefully have more happiness.

The importance of enjoying food

Eating medicine is not as fun as eating food, and turning food into medicine is downright depressing. Food is food; it nourishes us, gives us energy, keeps us alive, and is necessary to our existence. Enjoyment of food is essential and this study from the 1970s shows that. Thai and Swedish women were both given a traditional Thai meal. The Thai women absorbed almost 50% more iron from the meal than the Swedish women, who felt it was too spicy. Then the traditional meals for both groups were pureed into mush and eaten. Guess what? Iron absorption for both groups decreased by 70% — even when eating their own traditional food. Let’s face it – puree is just not as tasty as the original-textured food!

If you’re treating your food like medicine, holding your nose and shoving it in, or dutifully eating “healthy” food but wishing for something else instead, you’re doing your body and your mind a disservice. What you eat on a meal-by-meal basis is not as important as how you eat. Having a relaxed relationship to food, providing regular, reliable meals for yourself, allowing internal signals of hunger and fullness regulate your intake, and eating food you enjoy is healthy. This way of eating optimizes variety, which ensures good nutrition.

Medical Nutrition Therapy

There are certain disease conditions for which changing what you eat can help to manage that condition. But there is a big difference between disease management vs. disease prevention. Eating low sodium your whole life will not necessarily stave off high blood pressure. Eating no carbs will not ensure you will never get diabetes. Many diseases have a genetic component, and eating a certain way does not guarantee that you will not get a disease. However, feeding yourself regularly in a positive, non-diet way does support health and is great disease prevention.

While diet can help manage conditions, it rarely cures them. People with celiac disease must strictly avoid gluten, but this does not cure the disease. People with hypertension can reduce dietary sodium to help manage blood pressure but they also need to exercise, manage stress, and sometimes take actual medication. And you cannot cure cancer with food (I’m sorry, you just can’t). Food is important and will help keep someone with cancer alive while it receives actual medicine which really can cure.

It’s true that many foods have medicinal properties. Cinnamon may help lower blood sugar in diabetics. Turmeric may have anti-inflammatory properties. Here’s the problem: will you start to sprinkle cinnamon on everything you eat even if it doesn’t taste good? I love turmeric – in a few dishes. A little goes a long way. But studies often show that in order to show a direct benefit of the medicinal properties of these foods, you have to have large quantities of it – more than you’d want to eat of anything in a day. Also, what we know about the synergistic properties of foods can so far fit in a thimble. Isolating compounds for their magic properties is reductive thinking. Food compounds interact with one another and we’re only just starting to understand this better now. Again, getting a varied diet of foods you enjoy will help you to get some of everything you need.

I know Hippocrates said, “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food,” and back then that made sense when they didn’t have a lot of actual medicines. But now we’ve got another problem which is a world full of disordered eating, so maybe it’s time to back off this food-as-medicine idea for a while.

Food does not need to be medicine, especially in the absence of illness. Food just needs to be food – delicious, enjoyable, varied, reliable fuel for your body – because that’s how it serves us in the healthiest way possible.

Start your path to normal eating with my free guide, 5 Strategies to Stop Overeating

Dietitians Unplugged Podcast

Eating

The moment you decide to stop dieting, it may feel like the biggest relief ever. Perhaps you are tired of trying to trick your body into thinking it doesn’t need food, ignoring gnawing hunger pangs (and eventually bingeing), and obsessing over food. And perhaps all of that isn’t controlling your weight anymore anyway. So you decide quit dieting for good and learn to eat “normally.”

But then you find the process of learning to eat normally is not always so straightforward.

Eating without restriction at first can feel scary. Restriction can provide a sense of security and control. Trying to eat normally may feel like you are now “out of control.”

You might struggle with “getting it right” or listening to your body (and maybe your body isn’t talking to you right now). Years of dieting can totally fuck with your head and your stomach, and can make this whole process a lot harder.

There are two things that can make this process even harder: Perfectionism and Judgment.

Perfect is the enemy of good

As former dieters, our “success” depended so much on being perfect, getting the diet right, and never falling off the proverbial wagon. Isn’t that why everyone blames people for diet failure? They didn’t stick to the diet, they weren’t perfect enough, and therefore they didn’t achieve the results. Even though we know this isn’t a personal failure – that the state of dieting is a completely unnatural one, that nearly everyone fails at weight loss over the long term, and that it has nothing to do with willpower – we often persist in this idea that if we had just done it perfectly enough, it would have worked out differently.

Residual diet perfectionism may linger. Normal eating becomes just a new thing to perfect. But really, it isn’t. Ellyn Satter’s definition of what normal eating looks like:

Normal eating is going to the table hungry and eating until you are satisfied. It is being able to choose food you like and eat it and truly get enough of it – not just stop eating because you think you should. Normal eating is being able to give some thought to your food selection so you get nutritious food, but not being so wary and restrictive that you miss out on enjoyable food. Normal eating is giving yourself permission to eat sometimes because you are happy, sad or bored, or just because it feels good. Normal eating is mostly three meals a day, or four or five, or it can be choosing to munch along the way. It is leaving some cookies on the plate because you know you can have some again tomorrow, or it is eating more now because they taste so wonderful. Normal eating is overeating at times, feeling stuffed and uncomfortable. And it can be undereating at times and wishing you had more. Normal eating is trusting your body to make up for your mistakes in eating. Normal eating takes up some of your time and attention, but keeps its place as only one important area of your life. In short, normal eating is flexible. It varies in response to your hunger, your schedule, your proximity to food and your feelings.

There is room for a lot of mistake-making with normal eating. So make those mistakes and learn from all of them!

Misplaced judgment

Fear of judgment is understandable. No one wants to be judged unworthy! And that is often the reason we diet in the first place – to be judged worthy, or to avoid harsh judgment of our bodies.

But if you’ve been suppressing your weight with restriction, weight regain may be inevitable. It can be dismaying that when we start to listen to our bodies, they start to gain weight (for some, at least). Surely, you think, if I just learned to eat “normally,” I would have a “normal” sized body? (ideas about “normal” sized bodies can vary widely, too, making it a useless measurement)

So we look at our bodies that seem out of control and decide that it probably has something to do with our new way of eating, which also feels completely out of control. We start to apply the brakes to our eating here and there. We try to eat a bit less, or eat more “healthful” foods than we feel like – and voila, sneaky restriction has surfaced, starting the restrict-binge cycle all over again.

All of this behavior stems from the judgment we’re putting on our bodies and what we think they should or shouldn’t be doing. Next thing you know, eating normally doesn’t feel good at all, and it’s now not any easier than dieting was. Thanks judgment, you judgey asshole!

What can you do?

Before you decide you’ve done something wrong, try instead to roll with the wisdom of your body. Remind yourself why you quit diets in the first place. Imagine what your life would be like if you decided to live authentically, in alignment with your internal eating cues. And what your life would be life if you decided to respect your body, no matter what size it was.

On a practical level, eat real meals, starting with breakfast, that you would serve to a friend with a good appetite. Avoid serving yourself the smallest possible portions. Eat regularly throughout the day, and listen for hunger. Experiment with what it’s like to be different levels of full.

Make a lot of eating mistakes. Give yourself grace for having to learn to eat again.

Thank perfectionism and judgment for whatever they’ve helped you through in the past, and then kiss them goodbye. Neither of them have a place in your eating anymore.

Start your path to normal eating with my free guide, 5 Strategies to Stop Overeating

Eating

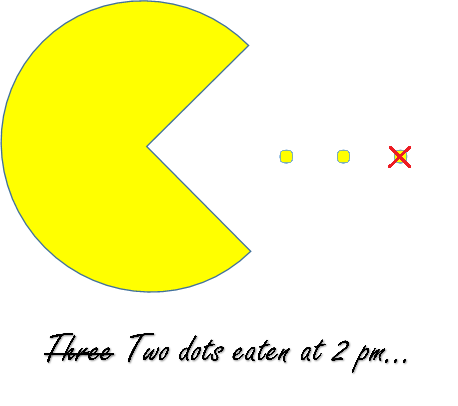

Pacman goes on a diet.

I was sick at home a few weeks ago and my appetite (along with my energy, my throat and my good humor) was shot. I didn’t feel like eating anything in particular, but I was still hungry and I knew I needed to put something on my stomach. I did what any sick person with no sense of smell and a craving for carby, starchy, sweet and/or cheesy foods would do – I picked and pecked at random selections of food for three days straight.

And suddenly I remembered ABC. If you’re a dieter, and maybe even specifically a Weight Watchers alum, you will know what ABC stands for. WW Leaders would chant this weekly to their loyal followers, reminding us why we might not be reaching our goal weights. “ABC – All Bites Count!” they would decree, and we’d nod our heads in unison.

Another way of saying this was “If you bite it, write it.” It means that literally every little bite you take must be logged into your journal. It means that no bite of food, no matter how innocuous seeming, no matter if it was a whole bite, or a half bite, or a measly nibble, should go unrecorded, because surely it will be that one bite that will take all your weight loss efforts down. Unless we stopped to figure out the points value of one quarter of an Oreo cookie and write it down, surely that one unrecorded bite might be the gateway drug to actually satisfying our appetites, and that would be the death knell of our weight loss. One cannot have a satisfied appetite and lose weight, we all knew that.

That’s how it eventually got for me, caught in the frenzy of weight loss and weight maintenance: seemingly innocent crumbs of foods here and there could not could not go unaccounted without worrying about how they would affect the scale the next week. And god forbid you end up getting sick, or divorced, or have a loved one who dies, or you lose a job, i.e. real life stuff…because those are prime pecking situations, and you are seriously not going to want to record anything when any of these happen (which explained why so many people dropped out when major life events occurred. Because you cannot diet and lose or maintain weight and still have a real life that can accommodate important stuff.)

And then there are those times, like at a party, when you have one bite, then another, and another and another and you think, “Oh what the hell, too many bites to remember, might as well go for broke,” and you eat so much that your belly hurts and you feel the shame of going so far off your diet that you’ll surely have to starve the rest of the week to make up for it.

What no one ever tells us is that even if we manage to write every single bite, we might not be happy or satisfied with either our eating OR our bodies. No one ever tells us, “95% of people who write down all their bites still regain most or all of their weight within three to five years after losing weight,” even though that is what all the current science tells us. No one seems to want to acknowledge that even if you are a super-bite-writer, a significant chunk of your life might be sucky because all you can think about is how you’re going to avoid the bites you might have to write. Because even if you are one of the miraculous 5% who maintain their weight loss longer than five years, your whole life will be dedicated to this one task.

Let’s be honest: having to account for every single bite you put in your mouth – whether it is “working” or not – is a fucked up way to live.

So although I was sick and sniffly and kind of miserable, I was really grateful for one thing: I didn’t have to worry about any of the bites. I could give my body the energy it was asking for, no questions asked, no bite-writing required. I’m going to stick with intuitive eating and eating competence because for me, that is eating well and enough and guilt-free. No more ABCs for me.

Dietitians Unplugged podcast – episode 6 available now!

Episode 6 is called “Clean Eating or Toxic Ideas?” and we had so much fun talking about this subject.

Listen on Libsyn or iTunes. Give us a review on iTunes if you like us — this helps to spread the non-diet love to more people. Check out our Facebook page for our latest episode and news and more weight neutral podcasts!

Subscribe and get my free guide:

Why you overeat …and what to do about it

Click here if you just want my newsletter!

Eating

![By AUGUST RODIN (Image:AUGUST_RODIN_O_pensador_(vista_frontal).jpg) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons PD-1923 Thinker, by August Rodin](https://daretonotdiet.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/thinker-medical-fail.png) I went to the doctor recently and this is the cheeky summation of how that went down:

I went to the doctor recently and this is the cheeky summation of how that went down:

Me: “I’m here for a totally not-fat-related-but-most-definitely-stress-related problem I have that I need to make sure isn’t something more than I think it is. I think the problem may resolve soon because my stress is decreasing due to my new less stressful job that I get to walk to vs. my previous unbearable commute… but in the meantime can you please tell me I’m not dying of something horrible even though it seems innocuous?”

Doctor: “That’s great that you’re walking to work. Maybe we’ll see that weight come down now.”

As much as I write about this stuff all the time, as much as I am abso-fucking-lutely okay with my body, this turn of conversation stunned me into momentary silence. How the hell did this turn into something about my weight? Especially when I had refused to even get on the scale this visit??

Make no mistake: weight bias is a real thing in health care. Scenes like this (and much worse) play out for fat people in doctors’ offices with alarming frequency, and often with more serious consequences. Sometimes visits to the doctor by fat people end in something like, “We will not provide this treatment for you until you lose weight.” Or, “The treatment for this fat-unrelated condition is to lose weight.”

For a long time, when I was not fat, I had forgotten the shame of being fat and going to the doctor. My first weight-related medical care incident occurred when I was 15 years old (and 20 pounds less than what I weigh now) and my doctor told me I was getting too fat (except he didn’t say the word “fat”) and that I needed to lose weight (and then offered up no further solutions). My mom was livid on my behalf (for reasons that only made sense to me much later in life, she was always worried I would develop an eating disorder), and I always wondered if she gave that doctor a talking-to, because he never brought it up again. My response was to refuse to be weighed at any appointments after that and thankfully, I didn’t go on a diet in my teens, a behavior that is well-known to have disastrous consequences, from the development of eating disorders to fucked up weight regulation lasting into adulthood.

Flash forward 30 years. Things are not better. In fact, thanks to rampant fat phobia, healthism and weight-based discrimination, weight bias in health care is a bigger problem than ever. I have worked in health care for the last three years and have witnessed this first-hand. Patients who need life-changing operations are being denied these operations based on their BMIs – and nothing else. In medical rounds, we discussed a dialysis patient with perfectly acceptable metabolic labs, who is by most standards healthy (aside from not having working kidneys) who won’t get a new, functioning kidney for one reason – his weight doesn’t fit into the completely arbitrary “normal” category on the BMI. People have been denied knee surgeries unless they can lose weight (read more about the topic of being fat and knee injuries here and here). A woman posted on my Facebook page that her doctor wanted to treat her muscular dystrophy with a 100-pound weight loss because he felt her muscles simply wouldn’t be able to accommodate her weight – despite the fact that weight loss is a catabolic process and will contribute to diminished muscle mass. Oh, and despite the fact that the science shows that the most probable long-term outcome of weight loss is eventual weight regain. Need more examples? Read here.

More than a few times, I was mortified by the utter disdain and lack of compassion shown by medical professionals for fat people who needed real, compassionate medical care. One skeptical doctor I know said, “I really don’t think weight bias is a big deal when there are so many other problems that are worse.” Well, yes, I suppose if you are not fat, this weight bias thing isn’t as big of a deal for you. But the existence of other problems does not diminish this problem. This is one of the big problems.

Now that I am technically “obese” (after having given up dieting in favor of a healthy relationship to food and my body), I don’t weigh myself again, not because I’m ashamed of my weight, but because the act of getting on the scale for so many years was fraught with anguish that I don’t wish to relive. I know generally what I weigh and I told my doctor my estimate when she asked. And that’s when, minutes later, she started haranguing me about losing some weight.

Once I had recovered my senses, I said to her, “I really don’t work on weight anymore. I just try to eat nutritiously and exercise and let my weight be what it will.” Still, she insisted, she felt my weight would decrease by walking to work more. She acted as though I hadn’t exercised a day in my life before this (I exercise regularly). I asked her if she had ever heard about Health at Every Size® – she hadn’t, but said it sounded fine when I explained to her. Then she apologized for offending me about my weight, and I had to explain that I wasn’t offended, but that I simply wasn’t interested in pursuing my weight as a health outcome. And that was that.

So I got off easy that day: I don’t have a life-threatening condition, and I am not large enough to attract the truly terrible treatment other larger people receive regularly. Although god forbid I need knee surgery some day in the future.

This clearly needs to change. We need doctors who are aware of the evidence around weight and health, or at least willing to hear it in the first place. We need doctors who are aware of their own bias against fat people.

Not everyone wants to be an activist, but I do encourage you to fight for your right to real, unbiased health care. If you’re looking for a fat-friendly physician, check out this list. If you already have a fat-friendly physician, consider adding yours to the list, because it’s not nearly long enough yet. For my part, I make sure I talk to every medical professional who will listen.

This free eBook Dealing at the Doctor’s Office by Ragen Chastain of the blog Dances with Fat may be helpful if you are dealing with these kinds of problems. Ragen’s blog is chock-full of information about being fat at the doctor’s (and I’ve already referenced some of that material here), so if you are looking for more on this topic, I suggest heading over there.

Let’s not stop fighting this together until everyone has the same access to medical care that everyone else does.

Dietitians Unplugged podcast – episode 6 available now!

Episode 6 is called “Clean Eating or Toxic Ideas?” and we had so much fun talking about this subject.

Listen on Libsyn or iTunes. Give us a review on iTunes if you like us — this helps to spread the non-diet love to more people. Check out our Facebook page for our latest news and more weight neutral podcasts!

Subscribe and get my free guide:

Why you overeat …and what to do about it

Click here if you just want my newsletter!

Eating

Check out episode 6 of the Dietitians Unplugged podcast in which Aaron and I discuss the “clean eating” trend. Is this just another way to eat, a diet, or a new religion? And what are the implications for the kids raised in this dichotomous way of thinking about food?

Check out episode 6 of the Dietitians Unplugged podcast in which Aaron and I discuss the “clean eating” trend. Is this just another way to eat, a diet, or a new religion? And what are the implications for the kids raised in this dichotomous way of thinking about food?

Here is the article that inspired this blog post. Warning: it includes fat-phobic comments and diet talk.

Other links referenced:

Ellyn Satter Institute

The Blessing Of A Skinned Knee: Using Jewish Teachings to Raise Self-Reliant Children, by Wendy Mogel, PhD

Listen on Libsyn or iTunes. Give us a review on iTunes if you like us — this helps to spread the non-diet love to more people. And feel free to like our new Facebook page!

Subscribe and get my free guide:

Why you overeat …and what to do about it

Click here if you just want my newsletter!

Eating

Hey everyone! Just thought I’d share my geeky excitement – I got to be a guest on Julie Dillon’s fantastic Love, Food podcast!

Hey everyone! Just thought I’d share my geeky excitement – I got to be a guest on Julie Dillon’s fantastic Love, Food podcast!

In this episode, a fat nutrition student writes a letter to food asking if she should go on a diet to better fit the mold of a dietetic student. Have a listen to how Julie and I answer the letter here.

You can subscribe to Julie’s Love, Food podcast on iTunes. Don’t forget to leave a review!

And…

A new Dietitians Unplugged Podcast episode coming very soon! Subscribe on iTunes to get the latest and leave us a review if you’ve been enjoying the podcast!

Subscribe and get my free guide:

Why you overeat …and what to do about it

Click here if you just want my newsletter!

Eating

![By Tripp (Flickr: Big Fat Cat) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons Big_Fat_Red_Cat](https://daretonotdiet.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/big_fat_red_cat.jpg)

I’m okay, you’re okay.

I was talking to an acquaintance who doesn’t know what I do (this body acceptance stuff) for at least some of my time, which is why she said to me, “I’m looking for a 1500 calorie diet – I saw pictures of myself at my nephew’s wedding and I didn’t like the way I looked. What diet should I do?”

Not being paid to treat her, I dispensed with any sort of motivational interviewing sensibility and pleaded, “Oh Harriet*! Please don’t even bother. Diets are horrible and in the end you just gain even more weight back.” She was interested in that, so we talked for a while about what all the science says and how food-and-calorie restriction just leads to crazy-eating and how in the end, almost no one loses weight forever.

But she kept coming back to one thing: I have to do something, because I’m just too big. Being a short, fat, older lady, she most likely receives confirmation, like all fat people, on a daily basis that she has the wrong body, if from nothing more than the near-total absence of fat bodies presented in every form of media that exists (but also probably from a lot more sources). I totally don’t blame her for getting stuck on this. I had talked about listening to our inner cues of hunger and satiety to regulate our eating, but that it probably wouldn’t make her thin. She concluded with, “I’ll try to listen to my hunger and fullness…but I also just need to have portion control,” which, sadly, is really just another way to say “diet.” And I totally get it, because the way she feels about her weight and needing to do something – yeah, I’ve been there.

So what I want to talk about today is not the massive failure of any sort of intentional weight loss effort, but rather the problem of body unhappiness. Because unless we at least explore the reasons for body dissatisfaction, it can be oh-so-hard to even contemplate achieving a peaceful relationship with food.

Why? Look at the above example. Harriet was interested in listening to her internal hunger and satiety cues (and she had a poignant story about childhood hunger that continues to fuel her need to overeat to this day) but she felt she needed to fix her body size first. She couldn’t get past it. She didn’t feel she had the right to exist happily in her body, no matter what her size. And we talked about the reasons for that too: the expectation of women that we always appear “attractive,” the lack of representation of fat bodies in the media, the weight loss industry who continues to perpetuate the idea that permanent weight loss is possible, the medical community who backs up this idea without acknowledging the overwhelming evidence that says that we don’t need to lose weight to be healthy, and society at large which says we need to lose weight to be happy. Everything that she’d ever heard told her that her fat body was wrong wrong wrong.

I think more than ever, thanks to this rampant fat-fear-mongering, so many of us have come to the conclusion that it’s NOT okay to 1. be in a fat body and 2. be happy with ourselves and our lives in that fat body. This is simply wrong.

So this is what I want you to know: you have the right to be happy in your body no matter what its size. You might be miles away from that, but you need to at least know that this is a possible outcome if you decide to choose it.

Permission is a powerful thing. We’re holding ourselves back from a fully-lived life when we feel we lack permission to be authentically ourselves. Your eating will suffer; your happiness will suffer; and your health will suffer.

Becoming happy in your fat body isn’t a quick trip. But you at the very least need the ticket – permission to be okay with your body – to get on board.

*Totally not her real name

Subscribe and get my free guide:

Why you overeat …and what to do about it

Click here if you just want my newsletter!